How 3D Game Rendering Works: Lighting and Shadows

The vast majority of visual furnishings you see in games today depend on the clever utilize of lighting and shadows -- without them, games would be tiresome and lifeless. In this fourth part of our deep expect at 3D game rendering, we'll focus on what happens to a 3D world alongside processing vertices and applying textures. It once again involves a lot of math and a sound grasp of the fundamentals of optics.

We'll dive right in to see how this all works. If this is your first time checking out our 3D rendering series, we'd recommend starting at the outset with our 3D Game Rendering 101 which is a basic guide to how one frame of gaming goodness is made. From there we've been working every aspect of rendering in the articles beneath...

Function 0: 3D Game Rendering 101

The Making of Graphics Explained

Part one: 3D Game Rendering: Vertex Processing

A Deeper Dive Into the World of 3D Graphics

Part 2: 3D Game Rendering: Rasterization and Ray Tracing

From 3D to Flat 2D, POV and Lighting

Office 3: 3D Game Rendering: Texturing

Bilinear, Trilinear, Anisotropic Filtering, Bump Mapping, More than

Part iv: 3D Game Rendering: Lighting and Shadows

The Math of Lighting, SSR, Ambient Apoplexy, Shadow Mapping

Part 5: 3D Game Rendering: Anti-Aliasing

SSAA, MSAA, FXAA, TAA, and Others

Epitomize

So far in the series we've covered the key aspects of how shapes in a scene are moved and manipulated, transformed from a 3-dimensional space into a apartment grid of pixels, and how textures are applied to those shapes. For many years, this was the majority of the rendering procedure, and we can come across this by going back to 1993 and firing up id Software'due south Doom.

The use of light and shadow in this title is very primitive by modernistic standards: no sources of lite are accounted for, every bit each surface is given an overall, or ambient, color value using the vertices. Any sense of shadows just comes from some clever use of textures and the designer's choice of ambient color.

This wasn't because the programmers weren't up to the job: PC hardware of that era consisted of 66 MHz (that's 0.066 GHz!) CPUs, 40 MB hard drives, and 512 kB graphics cards that had minimal 3D capabilities. Fast forward 23 years, and it's a very unlike story in the acclaimed reboot.

There'due south a wealth of technology used to return this frame, boasting cool phrases such every bit screen space ambience occlusion, pre-pass depth mapping, Bokeh blur filters, tone mapping operators, and then on. The lighting and shadowing of every surface is dynamic: constantly changing with ecology weather and the player's actions.

Since everything to do with 3D rendering involves math (and a lot of information technology!), nosotros better get stuck into what's going on behind the scenes of any modern game.

The math of lighting

To practise any of this properly, you need to be able to accurately model how light behaves as information technology interacts with unlike surfaces. You might be surprised to know that the origins of this dates back to the 18th century, and a human called Johann Heinrich Lambert.

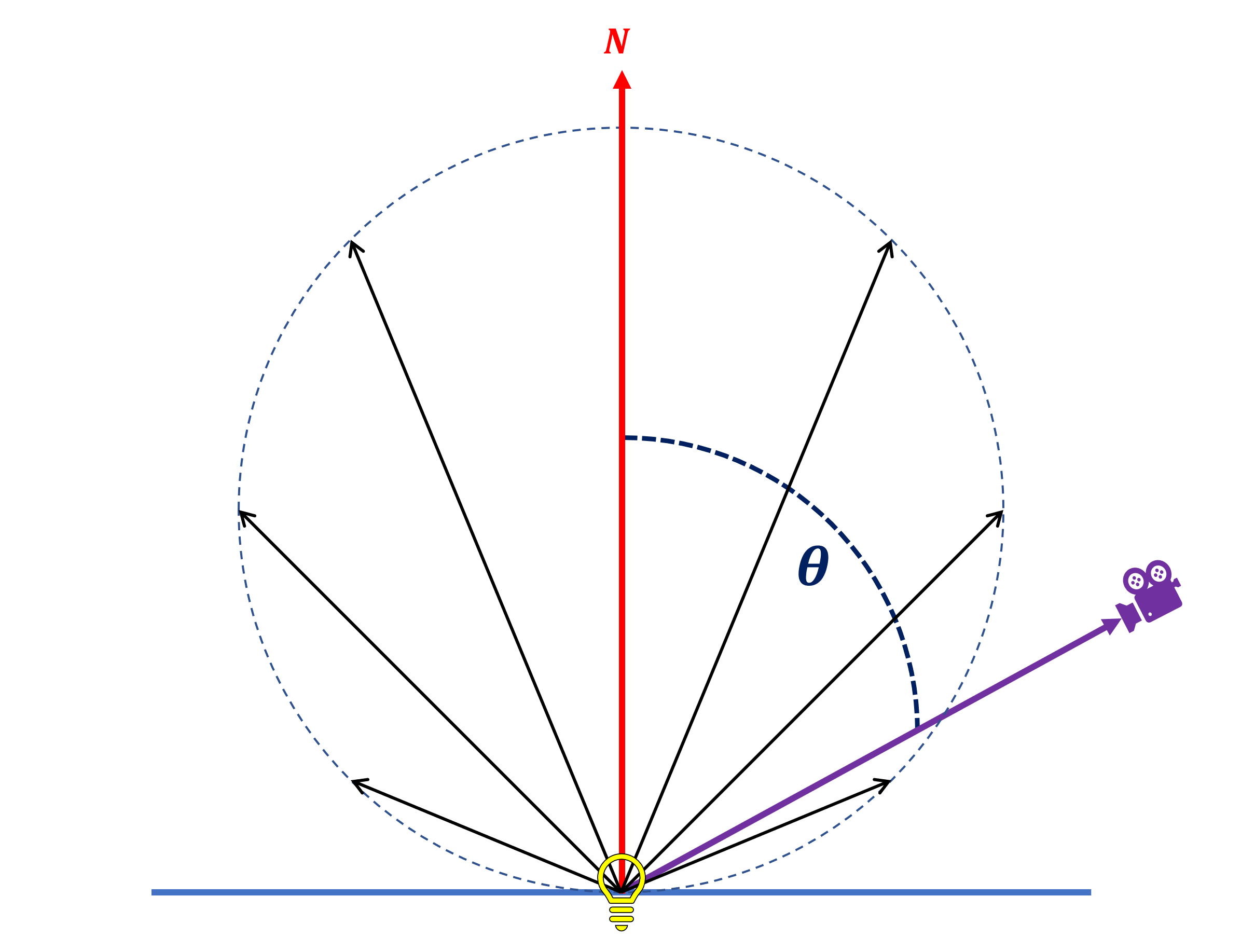

In 1760, the Swiss scientist released a book chosen Photometria -- in information technology, he gear up downwardly a raft of key rules about the behaviour of light; the most notable of which was that surfaces emit light (past reflection or as a light source itself) in such a mode that the intensity of the emitted light changes with the cosine of the angle, as measured between the surface's normal and the observer of the calorie-free.

This simple rule forms the footing of what is called lengthened lighting. This is a mathematical model used to summate the colour of a surface depending its physical properties (such as its color and how well it reflects light) and the position of the lite source.

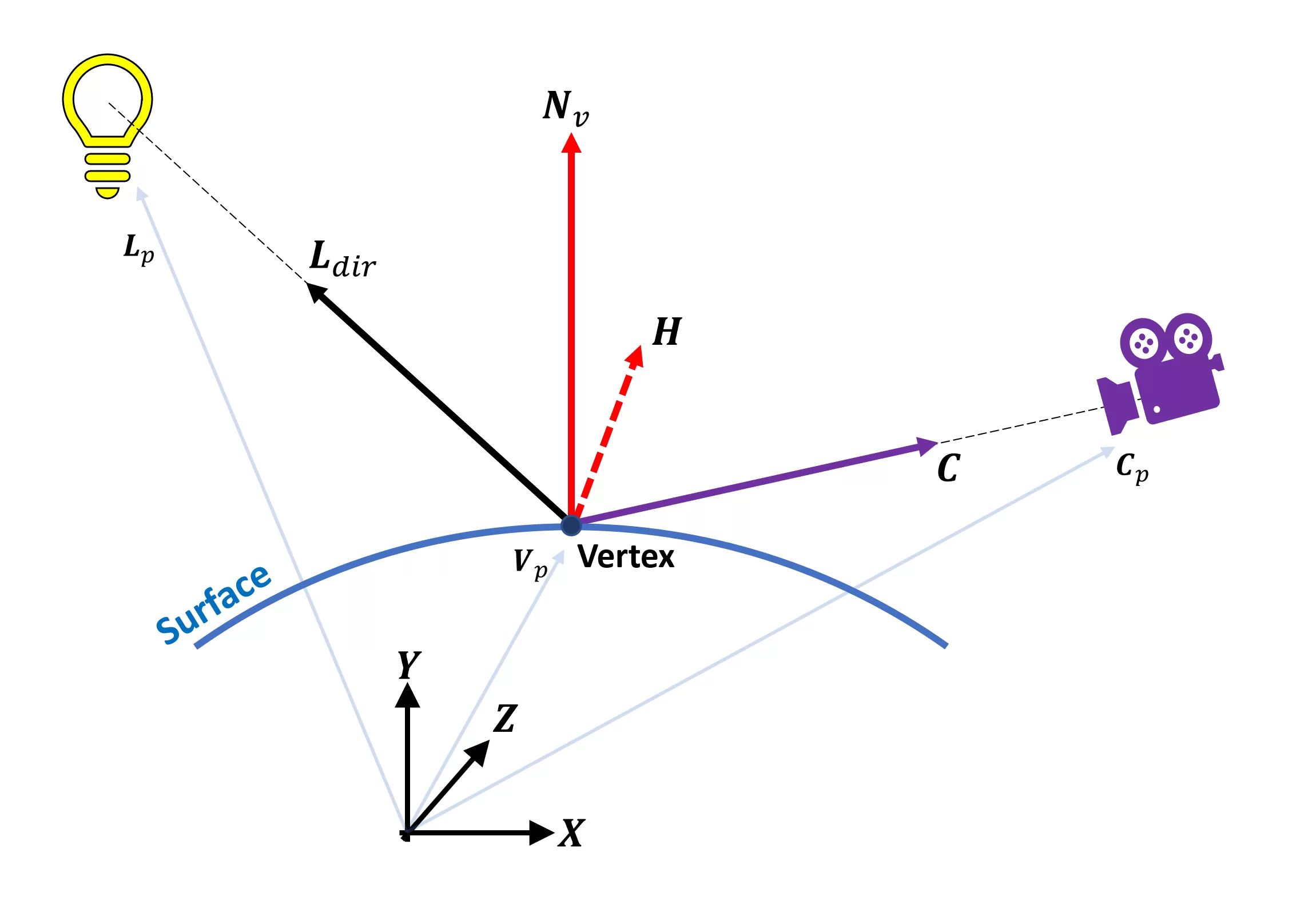

For 3D rendering, this requires a lot of information, and this can best be represented with another diagram:

You can come across a lot of arrows in the flick -- these are vectors and for each vertex to summate the colour of, there volition be:

- three for the positions of the vertex, light source, and camera viewing the scene

- 2 for the directions of the light source and camera, from the perspective of the vertex

- 1 normal vector

- one half-vector (it's ever halfway between the calorie-free and camera management vectors)

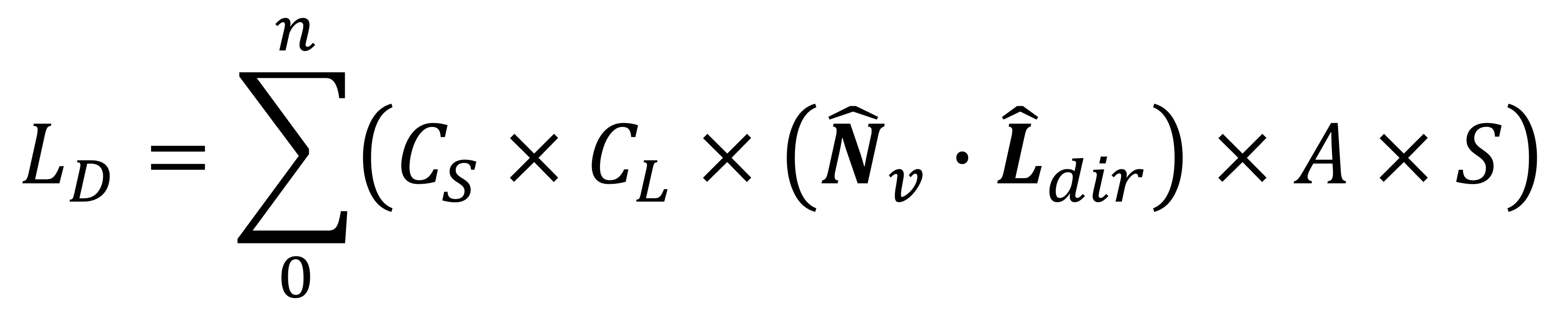

These are all calculated during the vertex processing stage of the rendering sequence, and the equation (called the Lambertian model) that links them all together is:

So the colour of the vertex, through diffuse lighting, is calculated by multiplying the color of the surface, the color of the light, and the dot product of the vertex normal and low-cal management vectors, with attenuation and spotlight factors. This is done for each light source in the scene, hence the 'summing' part at the start of the equation.

The vectors in this equation (and all of the rest we volition encounter) are normalized (as indicated past the accent on each vector). A normalized vector retains its original direction, but it's length is reduced to unity (i.e. it'south exactly 1 unit of measurement in magnitude).

The values for the surface and light colors are standard RGBA numbers (red, green, blue, alpha-transparency) -- they tin can be integer (e.g. INT8 for each color channel) only they're about always a float (e.g. FP32). The attenuation cistron determines how the light level from the source decreases with altitude, and it gets calculated with another equation:

The terms AC, AL, and AQ are diverse coefficients (constant, linear, quadratic) to describe the way that the light level is affected by distance -- these all take to be set out past the programmers when created the rendering engine. Every graphics API has its own specific mode of doing this, but the coefficients are entered when the blazon of light source is coded.

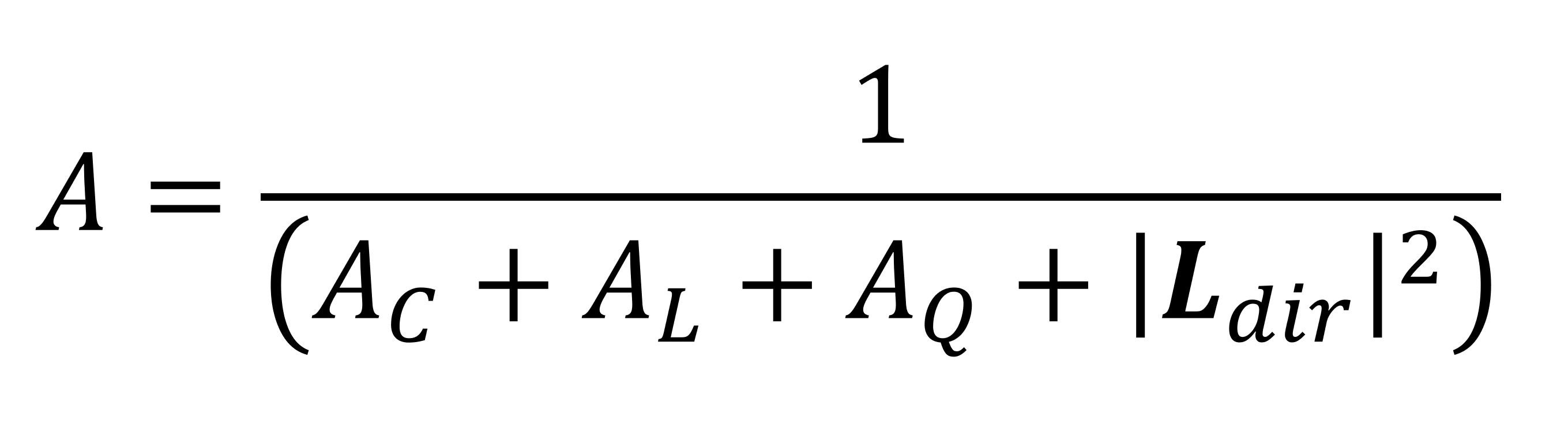

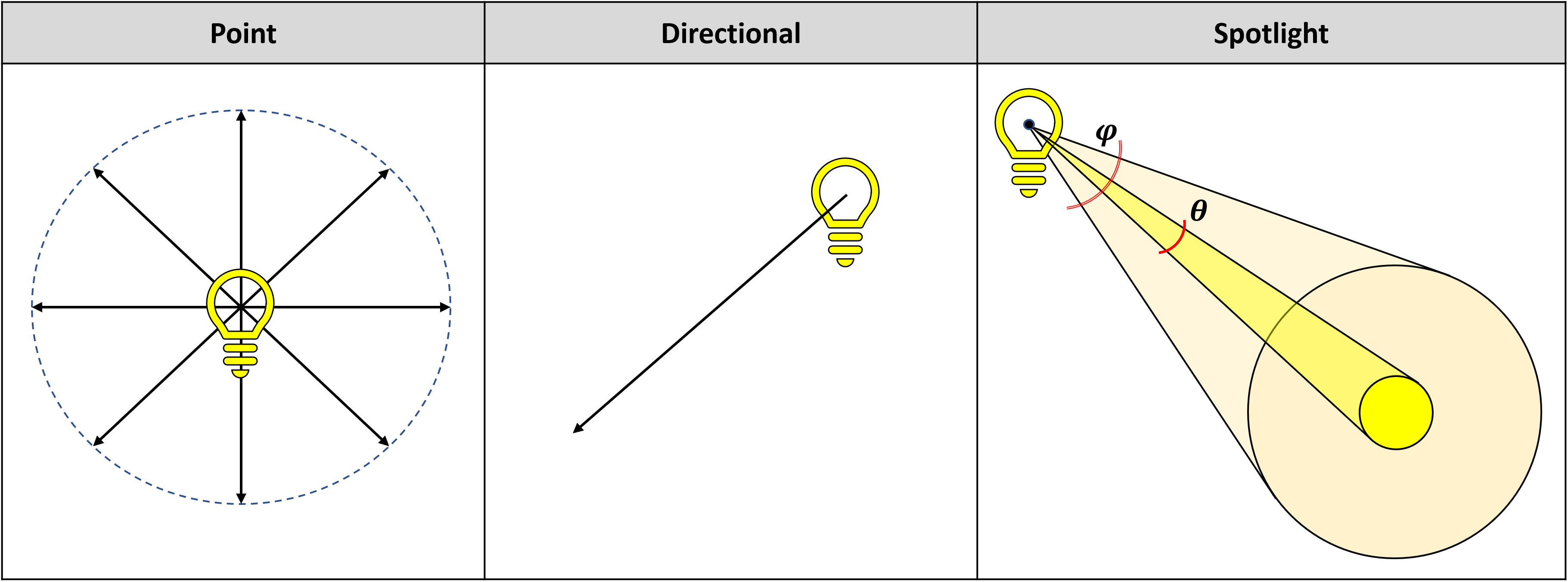

Before we look at the last gene, the spotlight i, it's worth noting that in 3D rendering, there are essentially 3 types of lights: bespeak, directional, and spotlight.

Point lights emit equally in all directions, whereas a directional lite merely casts light in one direction (math-wise, information technology'due south actually a point light an infinite distance away). Spotlights are complex directional sources, as they emit light in a cone shape. The way the light varies across the body of the cone is adamant the size of the inner and outer sections of cone.

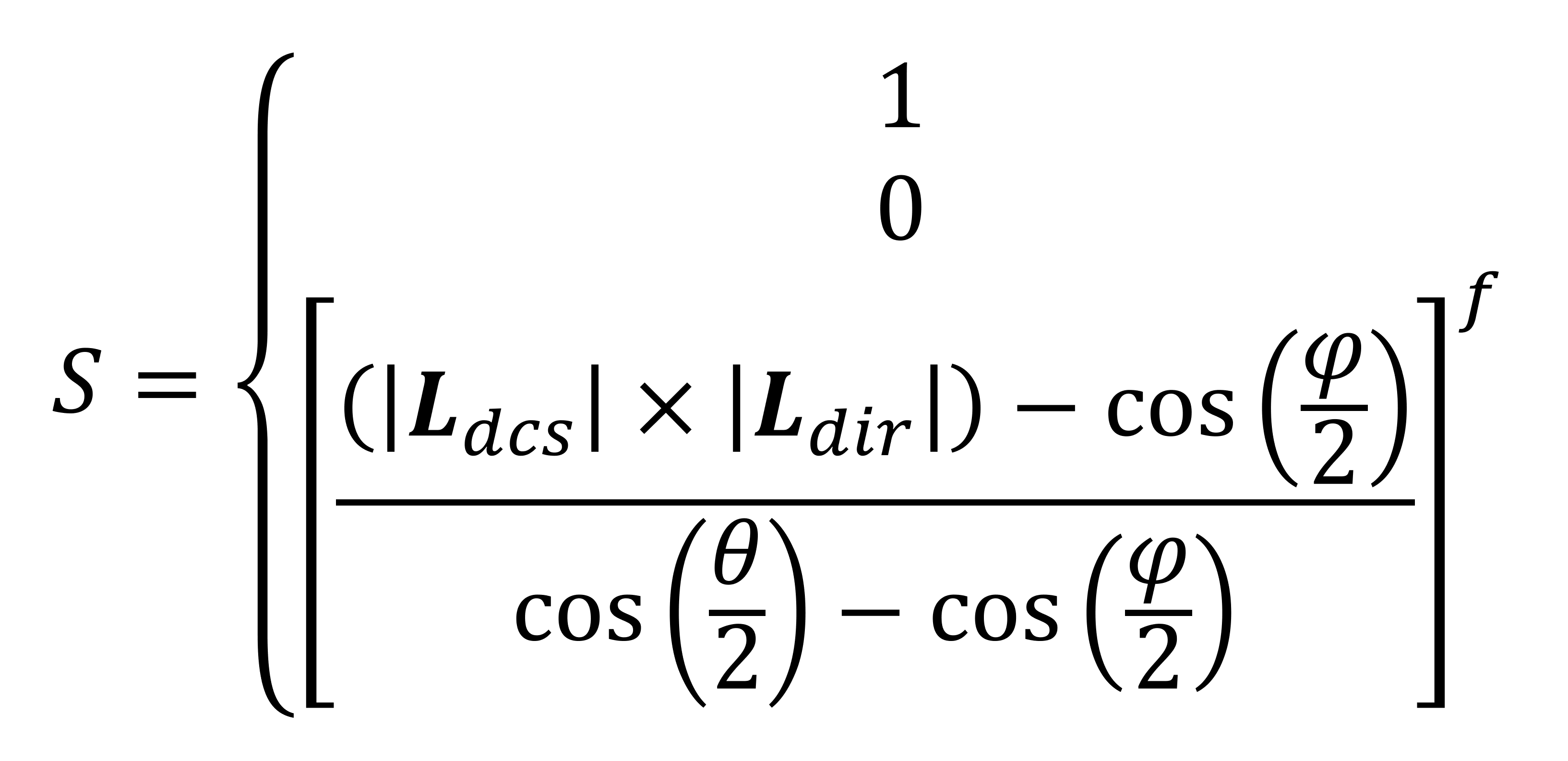

And yes, there'south another equation for the spotlight factor:

The value for the spotlight factor is either 1 (i.eastward. the calorie-free isn't a spotlight), 0 (if the vertex falls exterior of the cone'due south direction), or some calculated value betwixt the 2. The angles φ (phi) and θ (theta) set out the sizes of the inner/outer sections of the spotlight'due south cone.

The ii vectors, Ldcs and 50dir, (the reverse of the camera'southward direction and the spotlight's management, respectively) are used to decide whether or non the cone will actually bear upon the vertex at all.

Now call back that this is all for computing the diffuse lighting value and it needs to be done for every lite source in the scene or at least, every low-cal that the programmer wants to include. A lot of these equations are handled by the graphics API, but they tin can be done 'manually' past coders wanting finer control over the visuals.

However, in the real world, there is essentially an infinite number of light sources. This is because every surface reflects low-cal and and so each one will contribute to the overall lighting of a scene. Even at night, in that location is still some background illumination taking identify -- be it from afar stars and planets, or lite scattered through the temper.

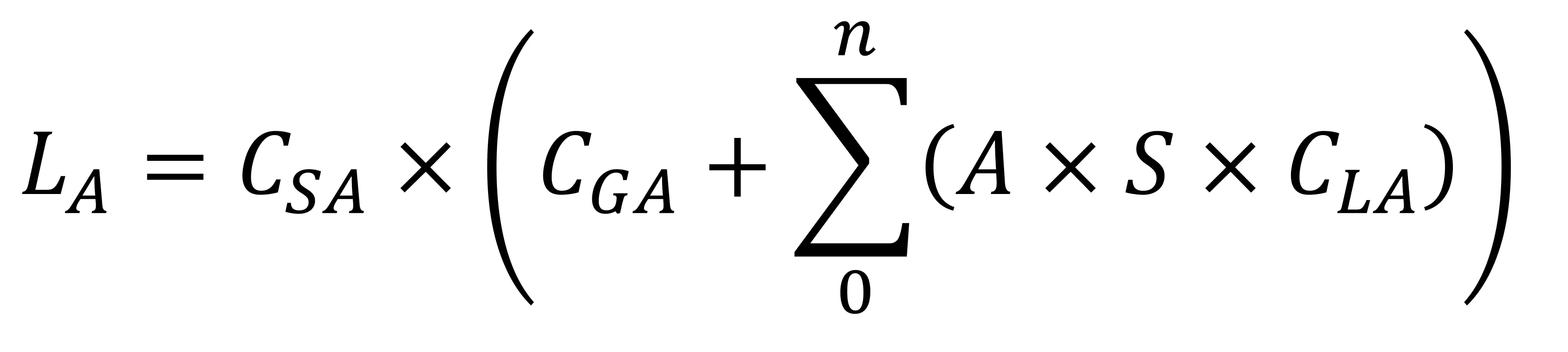

To model this, another light value is calculated: one called ambience lighting.

This equation is simpler than the diffuse one, because no directions are involved. Instead, it's a direct frontward multiplication of diverse factors:

- CSA -- the ambient color of the surface

- CGA -- the ambient color of the global 3D scene

- CLA -- the ambient color of any light sources in the scene

Annotation the apply of the attenuation and spotlight factors over again, along with the summation of all the lights used.

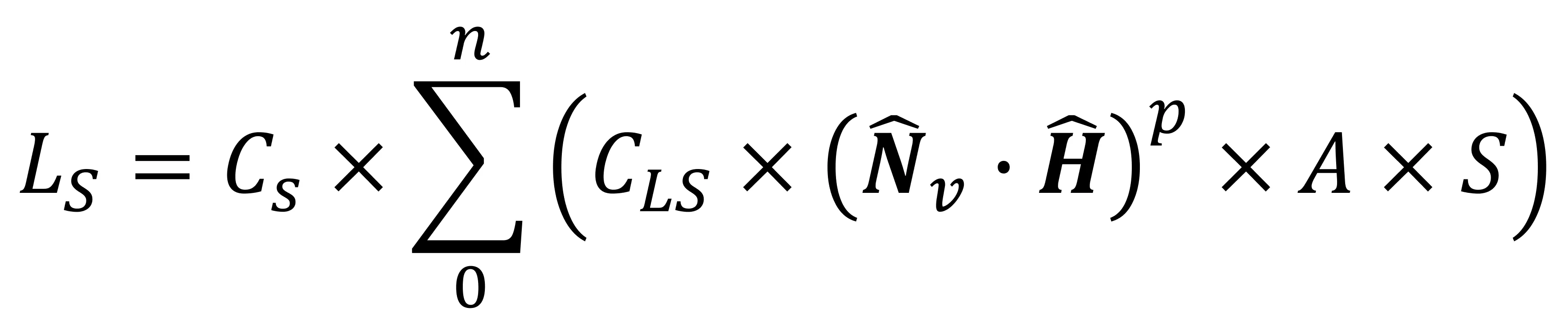

So we have background lighting and how calorie-free source diffusely reflect off the unlike surfaces in the 3D world all accounted for. But Lambert's approach really only works for materials that reflect low-cal off their surface in all directions; objects made from glass or metal will produce a dissimilar blazon of reflection, and this is called specular and naturally, there'south an equation for that, too!

The various aspects of this formula should be a piddling familiar now: we have two specular colour values (i for the surface, CS, and one for the light, CLS), also as the usual attenuation and spotlight factors.

Because specular reflection is highly focused and directional, ii vectors are used to determine the intensity of the specular calorie-free: the normal of the vertex and the half-vector. The coefficient p is chosen the specular reflection power, and it's a number that adjusts how bright the reflection will be, based on the textile properties of the surface. Equally the size of p increases, the specular outcome becomes brighter but more focused, and smaller in size.

The final lighting aspect to account for is the simplest of the lot, because it's but a number. This is called emissive lighting, and gets applied for objects that are a straight source of light -- e.grand. a flame, flashlight, or the Dominicus.

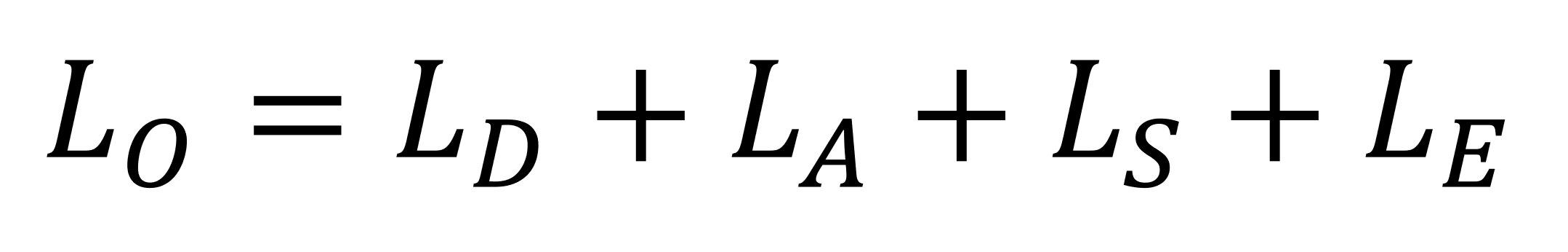

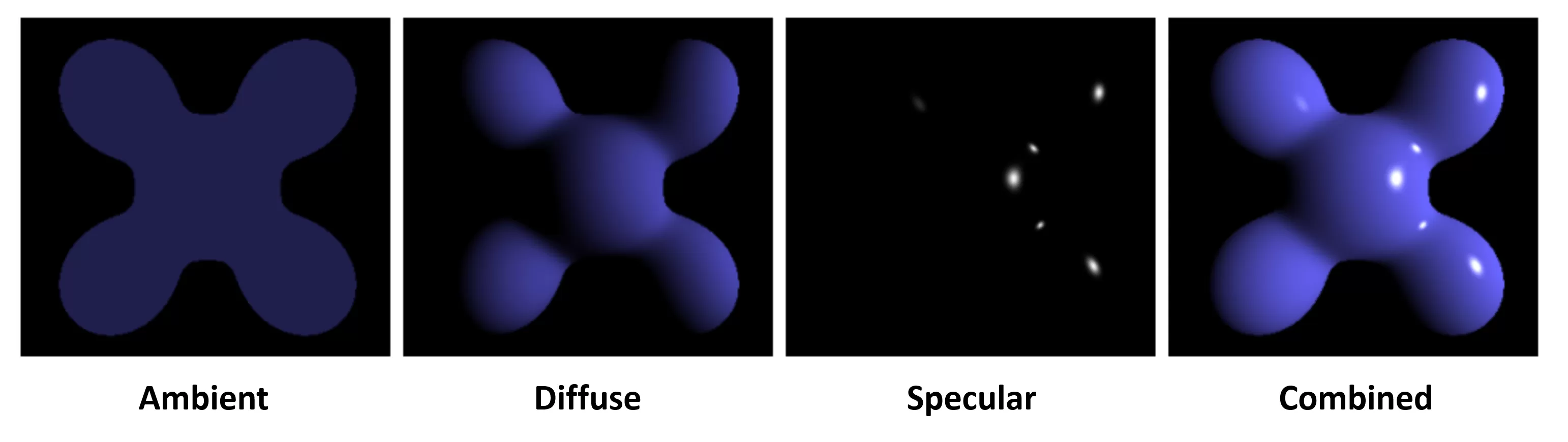

This means nosotros now take 1 number and 3 sets of equations to calculate the colour of a vertex in a surface, accounting for background lighting (ambient) and the interplay between various light sources and the textile backdrop of the surface (diffuse and specular). Programmers tin can choose to just employ one or combine all 4 by just adding them together.

Visually, the combination takes an appearance like this:

The equations we've looked at are employed by graphics APIs, such as Direct3D and OpenGL, when using their standard functions, merely at that place are alternative algorithms for each type of lighting. For case, diffuse can be done via the Oren-Nayar model which suits very rough surfaces between than Lambertian.

The specular equation earlier in this article tin can be replaced with models that business relationship for the fact that very smooth surfaces, such equally glass and metal, are even so rough simply on a microscopic level. Labelled as microfacet algorithms, they offering more realistic images, at a cost of mathematical complexity.

Whatsoever lighting model is used, all of them are massively improved by increasing the frequency with which the equation is applied in the 3D scene.

Per-vertex vs per-pixel

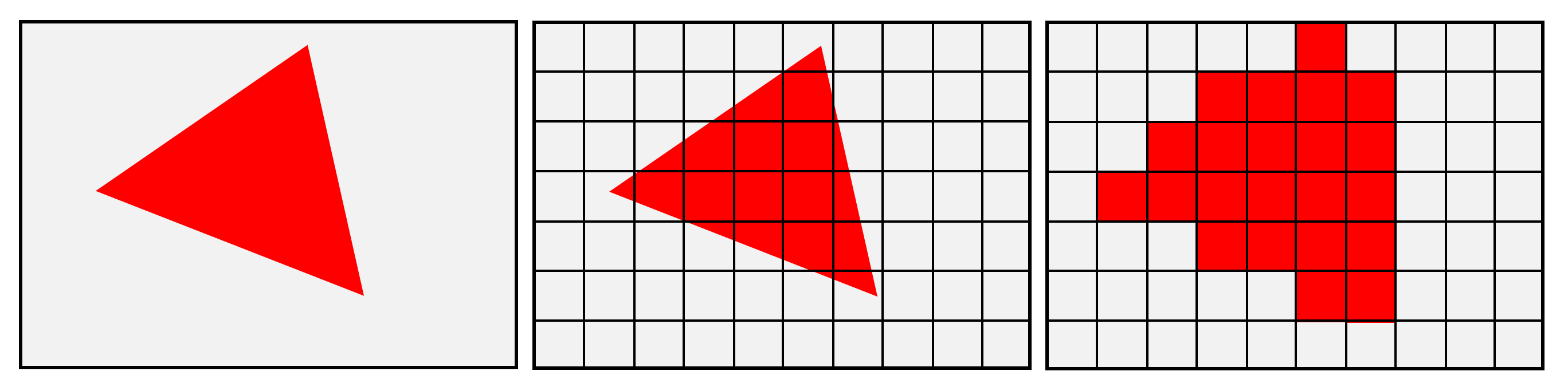

When nosotros looked at vertex processing and rasterization, nosotros saw that the results from all of the fancy lighting calculations, done on each vertex, have to be interpolated across the surface betwixt the vertices. This is because all of the backdrop associated the surface'south material are contained within the vertices; when the 3D world gets squashed into a 2nd grid of pixels, there volition only exist one pixel directly where the vertex is.

The remainder of the pixels will need to be given the vertex's color information in such a way that the colors blend properly over the surface. In 1971, Henri Gouraud, a post-graduate of University of Utah at the fourth dimension, proposed a method to do this, and it now goes by the proper name of Gouraud shading.

His method was computationally fast and was the de facto method of doing this for years, but it'south not without bug. Information technology struggles to interpolate specular lighting properly and if the shape is constructed from a depression number of primitives, then the blending between the primitives doesn't look right.

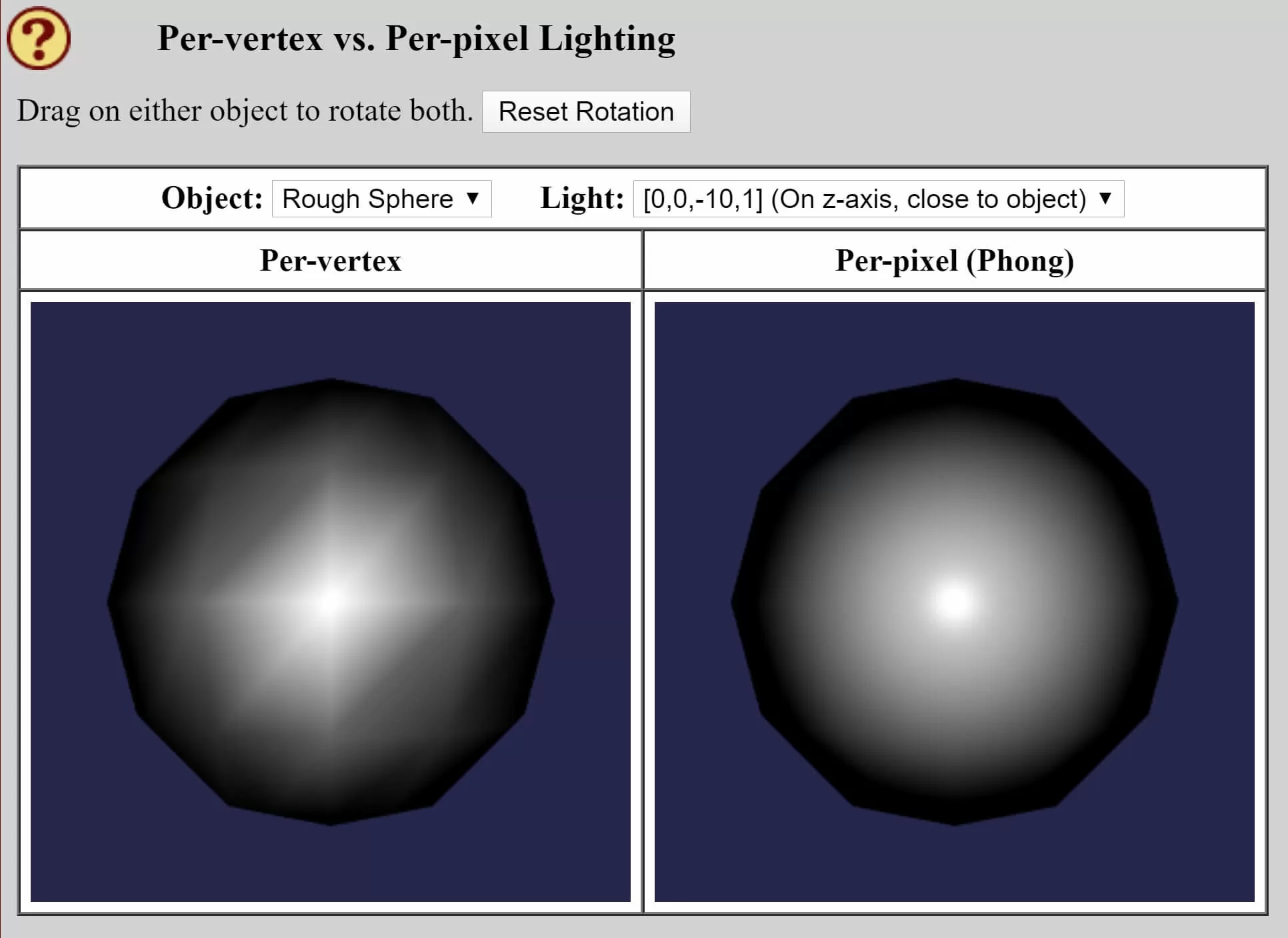

A solution to this problem was proposed by Bui Tuong Phong, also of Academy of Utah, in 1973 -- in his research paper, Phong showed a method of interpolating vertex normals on rasterized surfaces. This meant that diffuse and specular reflection models would piece of work correctly on each pixel, and we can meet this conspicuously using David Eck'south online textbook on computer graphics and WebGL.

The chunky spheres are beingness colored by the same lighting model, just the one on the left is doing the calculations per vertex so using Gouraud shading to interpolate it across the surface. The sphere on the right is doing this per pixel, and the departure is obvious.

The withal paradigm doesn't do enough justice to practice the improvement that Phong shading brings, but you tin try the demo yourself using Eck'south online demo, and see it animated.

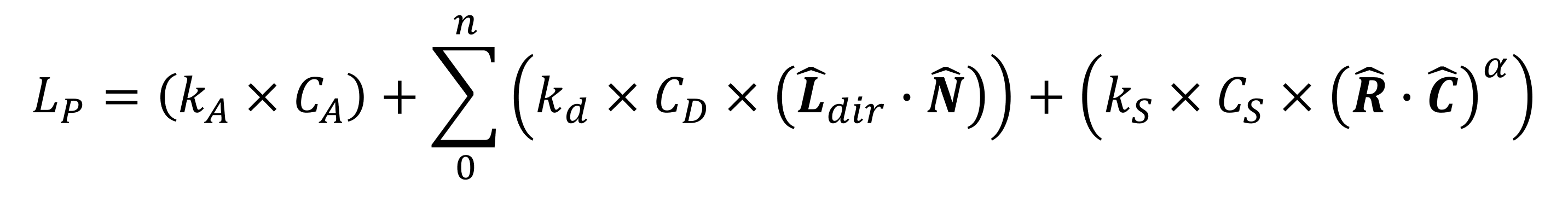

Phong didn't stop in that location, though, and a couple of years afterwards, he released some other inquiry paper in which he showed how the dissever calculations for ambience, diffuse, and specular lighting could all be done in i single equation:

Okay, so lots to go through here! The values indicated past the letter yard are reflection constants for ambient, diffuse, and specular lighting -- each one is the ratio of that particular blazon of light reflected to the amount of incident light; the C values we saw in the earlier equations (the color values of the surface material, for each lighting type).

The vector R is the 'perfect reflection' vector -- the direction the reflected light would accept, if the surface was perfectly smoothen, and is calculated using the normal of the surface and the incoming light vector. The vector C is the management vector for the photographic camera; both R and C are normalized likewise.

Lastly, in that location's 1 more constant in the equation: the value for α determines how shiny the surface is. The smoother the material (i.e. the more than glass/metal-like it is), the higher the number.

This equation is more often than not called the Phong reflection model, and at the time of the original inquiry, the proposal was radical, as it required a serious amount of computational power. A simplified version was created by Jim Blinn, that replaced the section in the formula using R and C, with H and Northward (the one-half-way vector and surface normal). The value of R has to be calculated for every light, for every pixel in a frame, whereas H only needs to be calculated in one case per light, for the whole scene.

The Blinn-Phong reflection model is the standard lighting system used today, and is the default method employed past Direct3D, OpenGL, Vulkan, etc.

There are enough more mathematical models out there, especially now that GPUs can procedure pixels through vast, circuitous shaders; together, such formulae are chosen bidirectional reflectance/transmission distribution functions (BRDF/BTFD for brusque) and they form the cornerstone of coloring in each pixel that we see on our monitors, when we play the latest 3D games.

However, we've but looked at surfaces reflecting light: translucent materials volition let low-cal to laissez passer through, and as it does so, the light rays are refracted. And sure surfaces, such as water, volition reverberate and transmit in each measures.

Taking light to the next level

Allow'southward take a wait at Ubisoft'due south 2022 title Assassin's Creed: Odyssey -- this game forces you to spend a lot of time sailing effectually on water, be it shallow rivers and coastal regions, likewise as deep seas.

To return the water as realistically equally possible, just likewise maintain a suitable level of performance, Ubisoft'south programmers used a gamut of tricks to brand it all piece of work. The surface of the water is lit via the usual trio of ambience, diffuse, and specular routines, simply there are some neat additions.

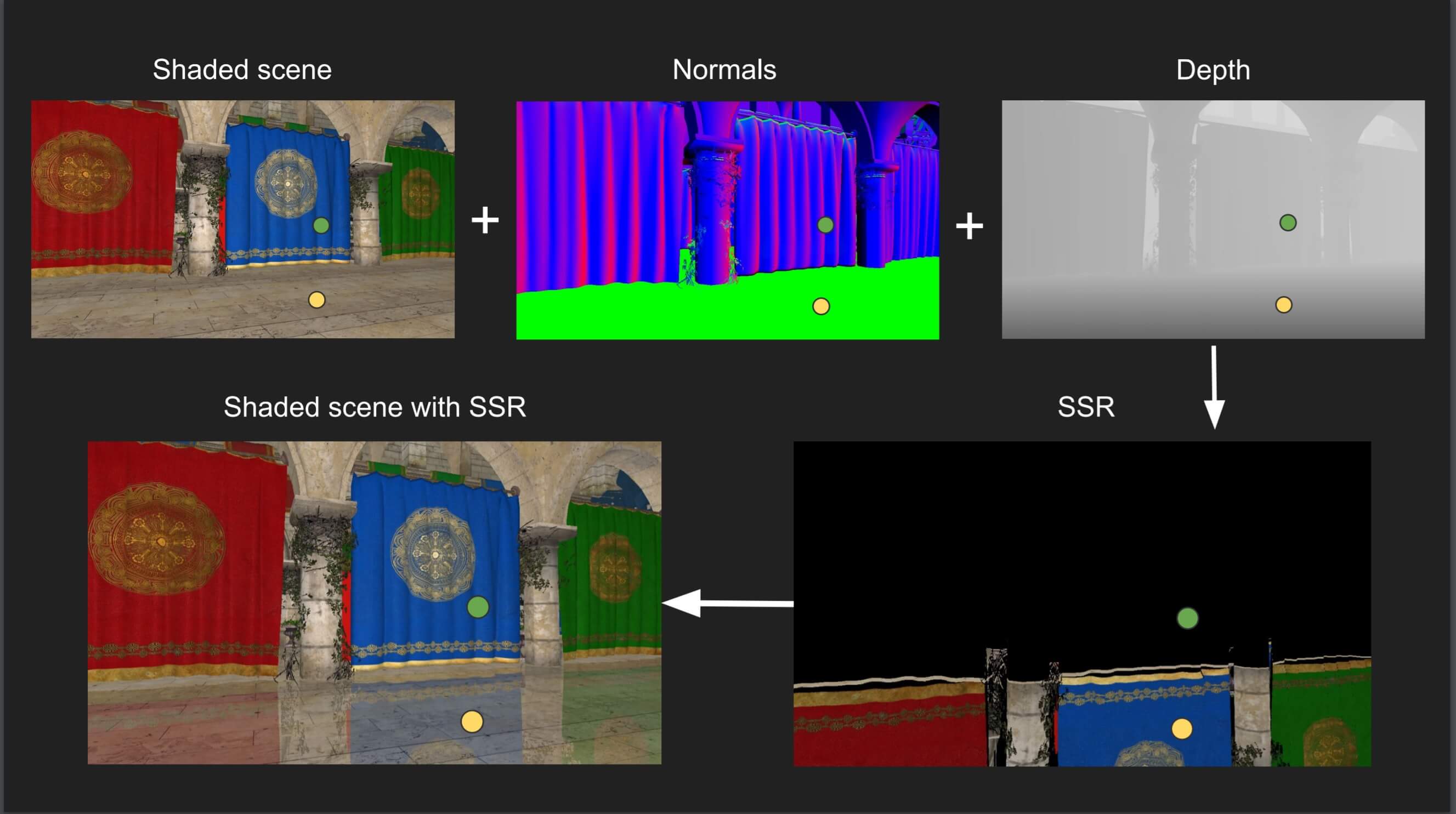

The first of which is commonly used to generate the reflective backdrop of h2o: southcreen space reflections (SSR for curt). This technique works by rendering the scene only with the pixel colors based on the depth of that pixel -- i.e. how far it is from the camera -- and stored in what's called a depth buffer. Then the frame is rendered over again, with the usual lighting and texturing, but the scene gets stored as a render texture, rather than the concluding buffer to be sent to the monitor.

After that, a spot of ray marching is done. This involves sending out rays from the camera and then at set stages along the path of the ray, code is run to cheque the depth of the ray confronting the pixels in the depth buffer. When they're the same value, the lawmaking and then checks the pixel's normal to see if it's facing the camera, and if information technology is, the engine then looks upwardly the relevant pixel from the render texture. A further set of instructions then inverts the position of the pixel, so that it is correctly reflected in the scene.

Calorie-free will as well scatter nigh when it travels through materials and for the likes of water and peel, another trick is employed -- this one is chosen sub-surface scattering (SSS). We won't go into any depth of this technique here but you can read more than well-nigh how information technology can be employed to produce amazing results, as seen beneath, in a 2022 presentation past Nvidia.

Going dorsum to water in Assassin's Creed, the implementation of SSS is very subtle, as information technology's non used to its fullest extent for operation reasons. In earlier Air conditioning titles, Ubisoft employed faked SSS merely in the latest release its utilise is more circuitous, though still not to the same extent that we tin can come across in Nvidia's demo.

Additional routines are done to modify the low-cal values at the surface of the water, to correctly model the effects of depth, by adjusting the transparency on the footing of distance from the shore. And when the camera is looking at the water close to the shoreline, all the same more than algorithms are processed to account for caustics and refraction.

The result is impressive, to say the least:

That's water covered, but what about every bit the light travels through air? Dust particles, moisture, and so on will likewise scatter the low-cal about. This results in light rays, every bit we see them, having volume instead of being only a collection of directly rays.

The topic of volumetric lighting could easily stretch to a dozen more articles by itself, so nosotros'll wait at how Rising of the Tomb Raider handles this. In the video below, in that location is 1 master low-cal source: the Sun, shining through an opening in the edifice.

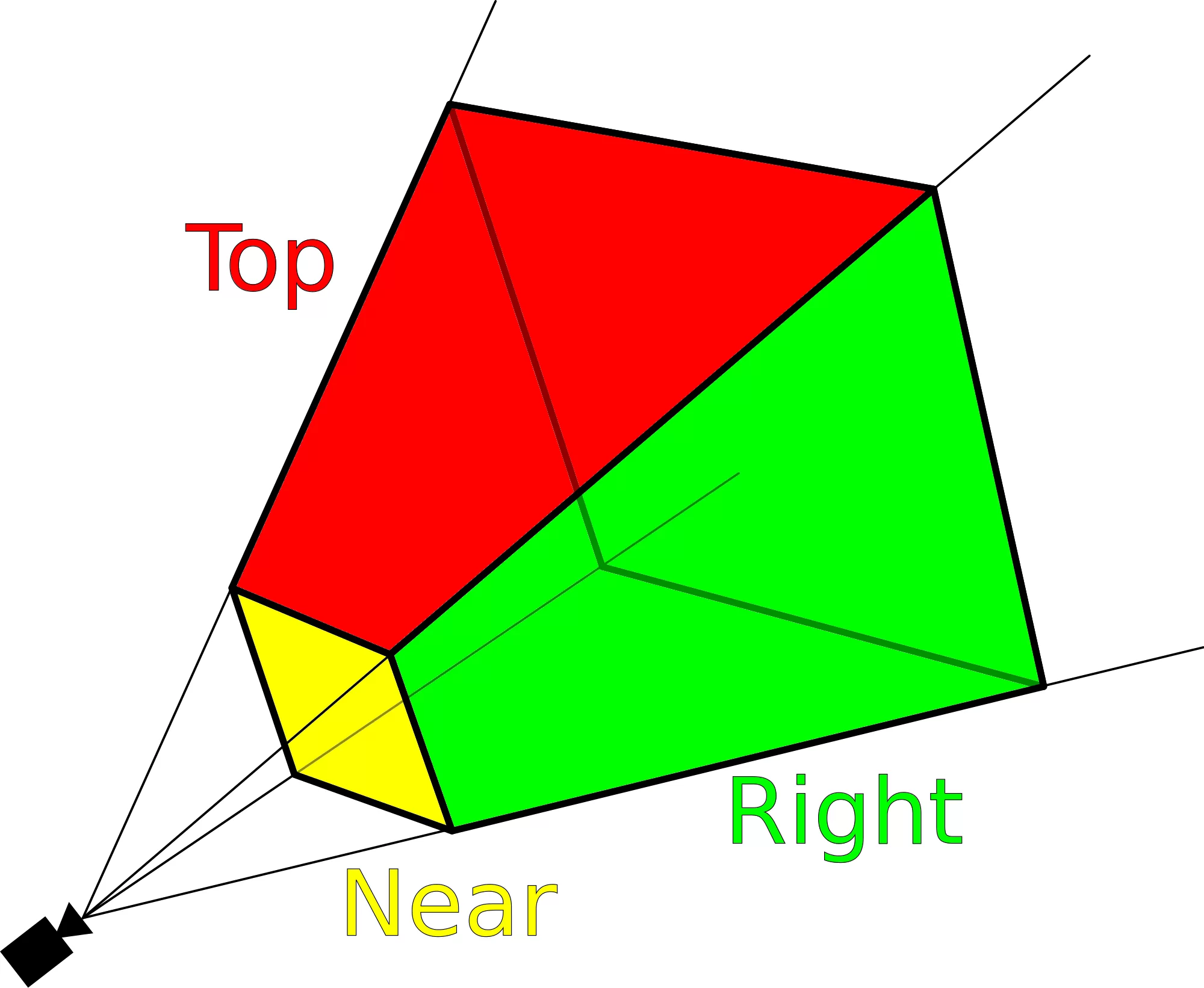

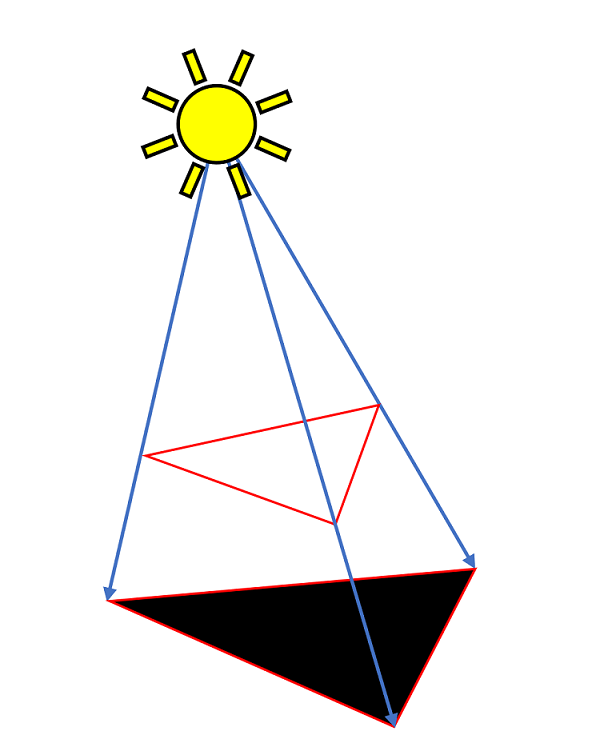

To create the volume of light, the game engine takes the camera frustum (encounter below) and exponentially slices it up on the ground of depth into 64 sections. Each slice is then rasterized into grids of 160 ten 94 elements, with the whole lot stored in a 3-dimensional FP32 render texture. Since textures are unremarkably 2D, the 'pixels' of the frustum volume are called voxels.

For a block of 4 10 4 x iv voxels, compute shaders determine which agile lights bear upon this book, and writes this data to another 3D render texture. A complex formula, known as the Henyey-Greenstein scattering role, is so used to estimate the overall 'density' of the light within the cake of voxels.

The engine then runs some more shaders to clean upward the information, earlier ray marching is performed through the frustum slices, accumulating the light density values. On the Xbox One, Eidos-Montréal states that this can all be done in roughly 0.viii milliseconds!

While this isn't the method used past all games, volumetric lighting is now expected in nigh all top 3D titles released today, specially first person shooters and action adventures.

Originally, this lighting technique was called 'god rays' -- or to give the right scientific term, crepuscular rays -- and one of the get-go titles to employ information technology, was the original Crysis from Crytek, in 2007.

It wasn't truly volumetric lighting, though, as the process involved rendering the scene as a depth buffer outset, and using information technology to create a mask -- another buffer where the pixel colors are darker the closer they are to the camera.

That mask buffer is sampled multiple times, with a shader taking the samples and blurring them together. This result is so blended with the concluding scene, every bit shown beneath:

The development of graphics cards in the past 12 years has been colossal. The most powerful GPU at the time of Crysis' launch was Nvidia's GeForce 8800 Ultra -- today's fastest GPU, the GeForce RTX 2080 Ti has over thirty times more computational power, xiv times more memory, and 6 times more bandwidth.

Leveraging all that computational power, today'due south games can practise a much better task in terms of visual accuracy and overall functioning, despite the increase in rendering complexity.

But what the effect is truly demonstrating, is that as important as correct lighting is for visual accuracy, the absenteeism of low-cal is what actually makes the difference.

The essence of a shadow

Permit's use the Shadow of the Tomb Raider to start our next department of this article. In the image beneath, all of the graphics settings related to shadows have been disabled; on the correct, they're all switched on. Quite the difference, right?

Since shadows occur naturally effectually us, any game that does them poorly will never wait right. This is because our brains are tuned to use shadows equally visual references, to generate a sense of relative depth, location, and move. Simply doing this in a 3D game is surprisingly difficult, or at the very least, hard to do properly.

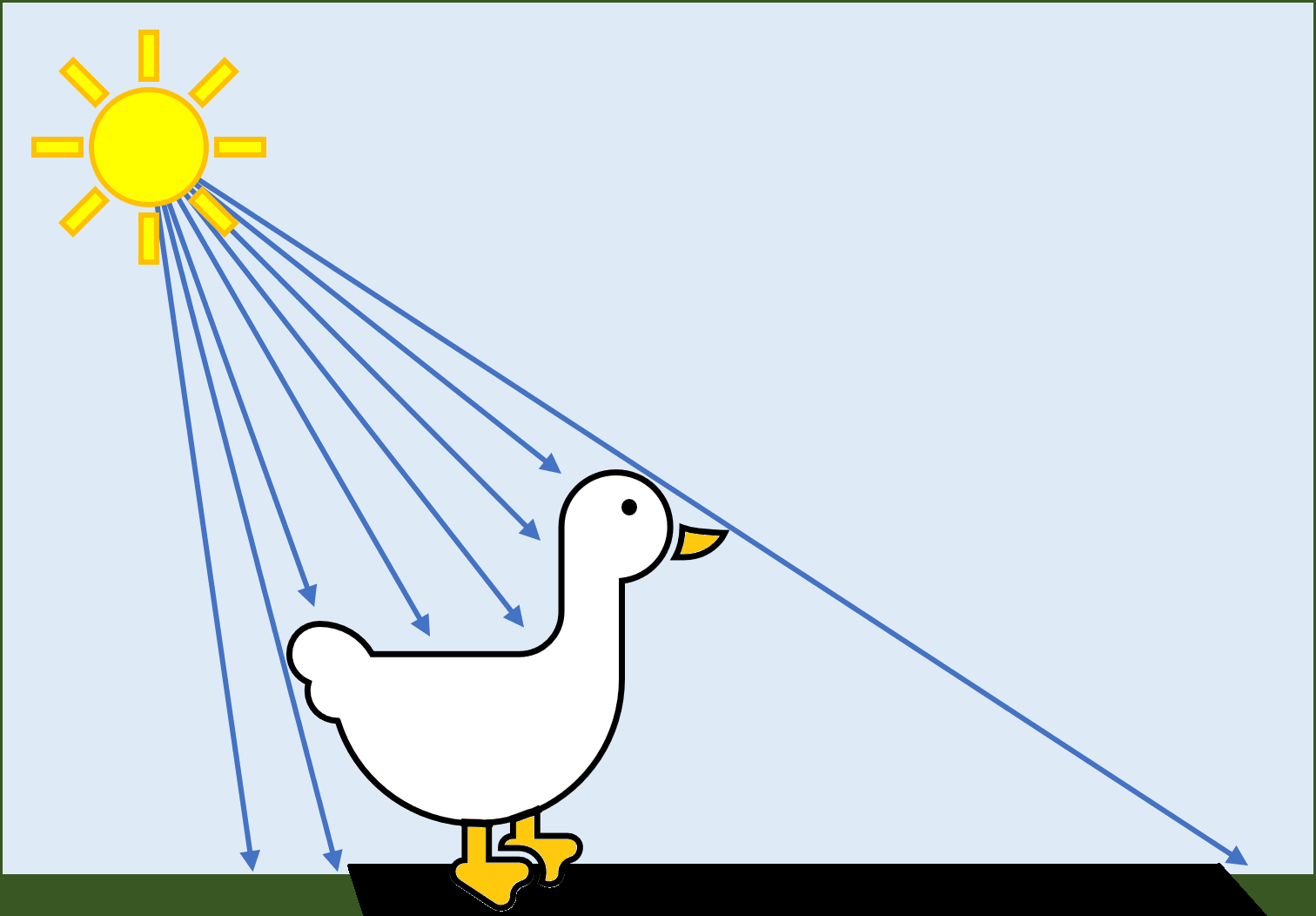

Let's starting time with a TechSpot duck. Here she is waddling about in a field, and the Sun's low-cal rays reach our duck and go blocked equally expected.

One of the earliest methods of adding a shadow to a scene similar this would exist to add together a 'blob' shadow underneath the model. It'southward not remotely realistic, as the shape of the shadow has nothing to do with shape of the object casting the shadow; nonetheless, they're quick and simple to do.

Early on 3D games, similar the 1996 original Tomb Raider game, used this method every bit the hardware at the time -- the likes of the Sega Saturn and Sony PlayStation -- didn't have the adequacy of doing much improve. The technique involves drawing a simple collection of primitives just above the surface the model is moving on, and then shading it all dark; an culling to this would be to describe a elementary texture underneath.

Another early method was shadow projection. In this process, the primitive casting the shadow is projected onto the plane containing the floor. Some of the math for this was developed by Jim Blinn, in the late 80s. It's a elementary process, by today'due south standards, and works best for elementary, static objects.

But with some optimization, shadow project provided the first decent attempts at dynamic shadows, as seen in Interplay's 1999 title Kingpin: Life of Crime. As we can see below, simply the blithe characters (including rats!) have shadows, but information technology's meliorate than simple blobs.

The biggest issues with them are: (a) the total opaqueness of the actual shadow and (b) the projection method relies on the shadow being cast onto a single, flat plane (i.e. the ground).

These problems could be resolved applying a caste of transparency to coloring of the projected primitive and doing multiple projects for each character, but the hardware capabilities of PCs in the late 90s simply weren't upwards to the demands of the extra rendering.

The modernistic engineering behind a shadow

A more authentic style to practise shadows was proposed much earlier than this, all the way back in 1977. Whilst working at the University of Austin, Texas, Franklin Crow wrote a inquiry paper in which he proposed several techniques that all involved the use of shadow volumes.

Generalized, the process determines which primitives are facing the light source, and the edges of these are extended are extended onto a airplane. So far, this is very much like shadow project, merely the key deviation is that the shadow volume created is then used to cheque whether a pixel is inside/outside of the volume. From this data, all surfaces can exist now be cast with shadows, and not but the ground.

The technique was improved by Tim Heidmann, whilst working for Silicon Graphics in 1991, farther still by Mark Kilgard in 1999, and for the method that we're going to wait at, John Carmack at id Software in 2000 (although Carmack's method was independently discovered 2 years earlier by Bilodeau and Songy at Artistic Labs, which resulted in Carmack tweaking his code to avoid lawsuit hassle).

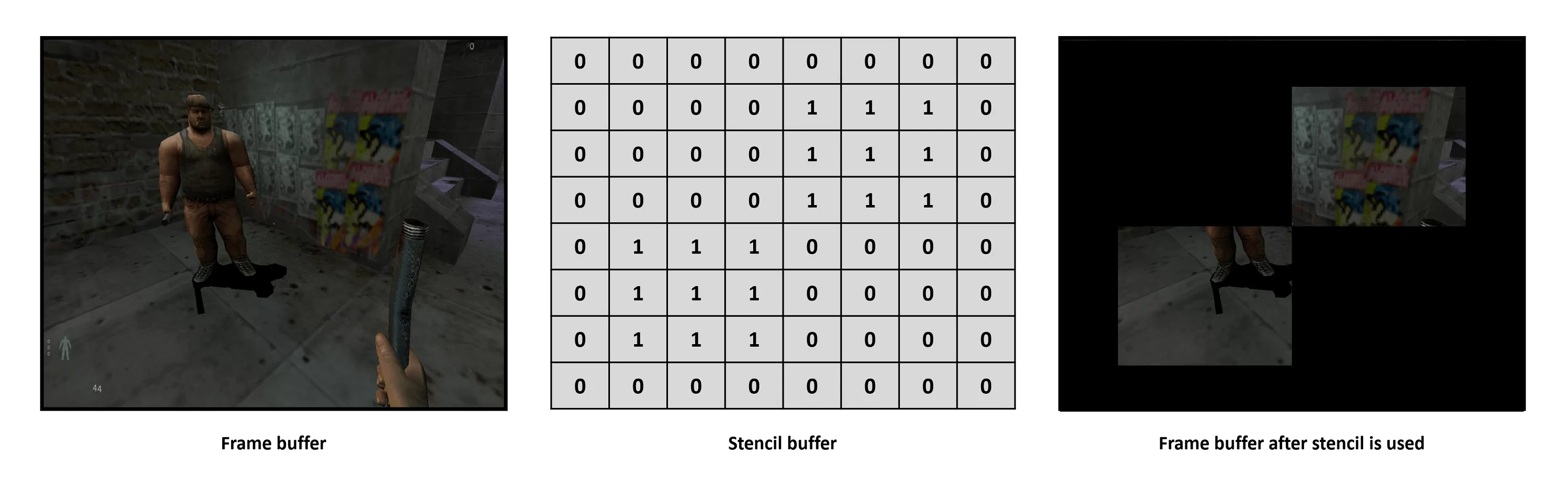

The approach requires the frame to be rendered several times (known every bit multipass rendering -- very enervating for the early 90s, only ubiquitous now) and something chosen a stencil buffer.

Unlike the frame and depth buffers, this isn't created by the 3D scene itself -- instead, the buffer is an array of values, equal in dimensions (i.e. same x,y resolution) as the raster. The values stored are used to tell the rendering engine what to do for each pixel in the frame buffer.

The simplest employ of the buffer is every bit a mask:

The shadow volume method goes something like this:

- Return the scene into a frame buffer, just only use ambient lighting (besides include any emission values if the pixel contains a calorie-free source)

- Render the scene again just but for surfaces facing the camera (aka dorsum-face culling). For each light source, calculate the shadow volumes (like the projection method) and check the depth of each frame pixel against the volume's dimensions. For those inside the shadow volume (i.east. the depth exam has 'failed'), increase the value in stencil buffer corresponding to that pixel.

- Echo the in a higher place, simply with front end-face culling enabled, and the stencil buffer entries decreased if they're in the volume.

- Return the whole scene again, but this time with all lighting enabled, only so blend the final frame and stencil buffers together.

We can encounter this use of stencil buffers and shadow volumes (commonly called stencil shadows) in id Software's 2004 release Doom iii:

Notice how the path the graphic symbol is walking on is still visible through the shadow? This is the first comeback over shadow projections -- others include being able to properly account for distance of the light source (resulting in fainter shadows) and existence cast shadows onto whatever surface (including the character itself).

But the technique does have some serious drawbacks, the most notable of which is that the edges of the shadow are entirely dependent on the number of primitives used to brand the object casting the shadow. This, and the fact that the multipass nature involves lots of read/writes to the local memory, tin can make the utilize of stencil shadows a little ugly and rather costly, in terms of performance.

There'due south also a limit to the number of shadow volumes that tin can exist checked with the stencil buffer -- this is because all graphics APIs allocate a relatively depression number of bits to it (typically only 8). The performance cost of stencil shadows usually stops this problem from ever actualization though.

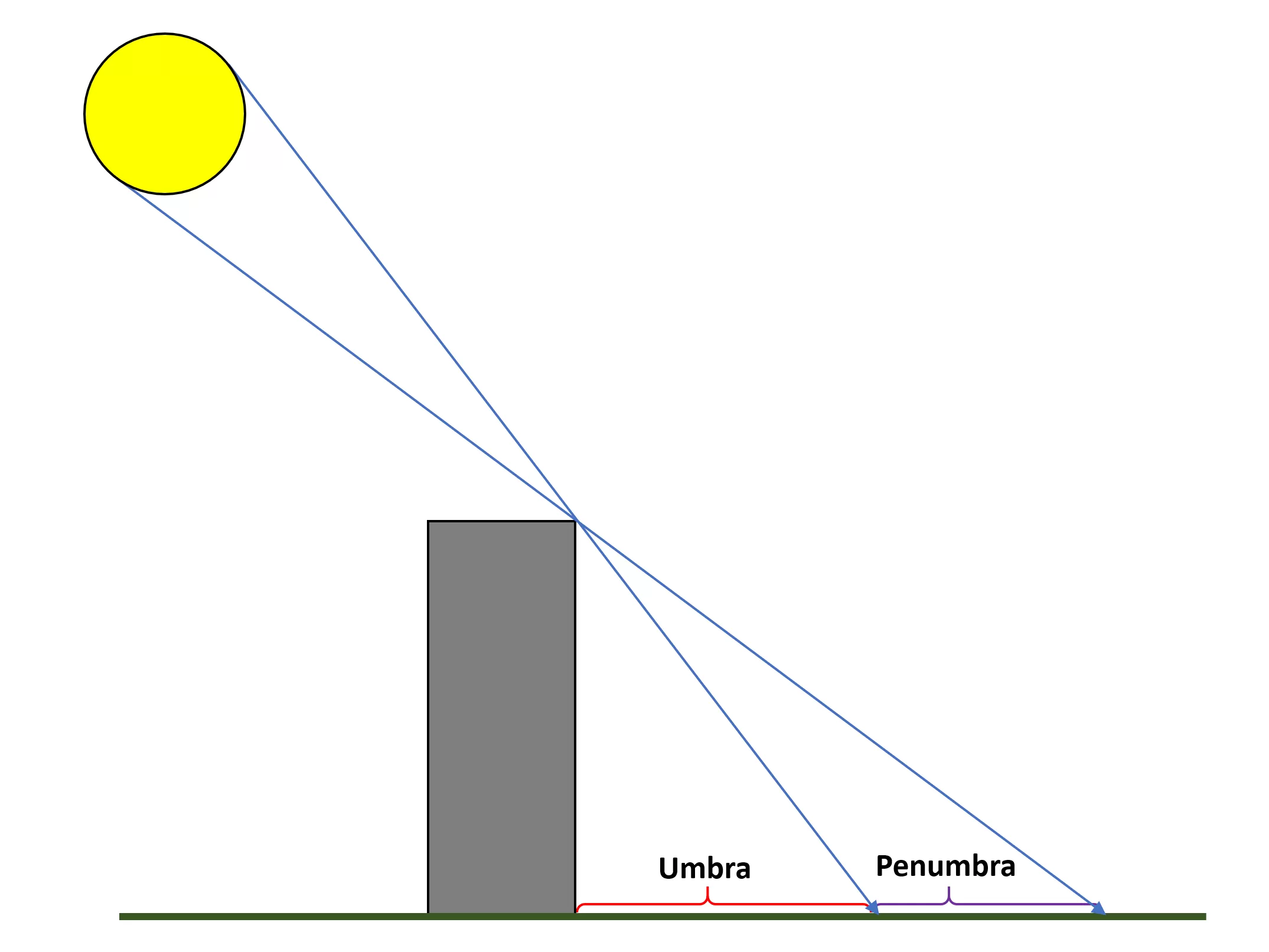

Lastly, there's the event that the shadows themselves aren't remotely realistic. Why? Because all low-cal sources, from lamps to fires, flashlights to the Lord's day, aren't single points in space -- i.e. they emit low-cal over an area. Even if i takes this to its simplest level, every bit shown below, existent shadows rarely have a well defined, hard edge to them.

The darkest area of the shadows is chosen the umbra; the penumbra is always a lighter shadow, and the purlieus between the ii is often 'fuzzy' (due to the fact that in that location are lots of lite sources). This can't be modelled very well using stencil buffers and volumes, as the shadows produced aren't stored in a manner that they can be processed. Enter shadow mapping to the rescue!

The basic process was developed by Lance Williams in 1978 and it'south relatively simple:

- For each light source, render the scene from the perspective of the calorie-free, creating a special depth texture (so no color, lighting, texturing, etc). The resolution of this buffer doesn't have to be aforementioned every bit the last frame's, but higher is better.

- Then render the scene from the photographic camera's perspective, but one time the frame has been rasterized, each pixel'south position (in terms of x,y, and z) is transformed using a light source as the coordinate system's origin.

- The depth of the transformed pixel is compared to corresponding pixel in the stored depth texture: if information technology's less, the pixel volition be a shadow and doesn't get the full lighting procedure.

This is obviously another multipass process, only the last stage tin can be done using pixel shaders such that the depth cheque and subsequent lighting calculations are all rolled into the same pass. And because the whole shadowing process is independent of how primitives are used, it's much faster than using the stencil buffer and shadow volumes.

Unfortunately, the bones method described above generates all kinds of visual artifacts (such equally perspective aliasing, shadow acne, 'peter panning'), well-nigh of which circumduct around the resolution and bit size of the depth texture. All GPUs and graphics APIs have limits to such textures, so a whole raft of additional techniques have been created to resolve the issues.

Ane advantage of using a texture for the depth information, is that GPUs accept the ability to sample and filter them very chop-chop and via a number of ways. In 2005, Nvidia demonstrated a method to sample the texture so that some of the visual problems caused past standard shadow mapping would exist resolved, and information technology besides provided a degree of softness to the shadow's edges; the technique is known as percentage closer filtering.

Around the same fourth dimension, Futuremark demonstrated the use of cascaded shadow maps (CSM) in 3DMark06, a technique where multiple depth textures, of different resolutions, are created for each light source. Higher resolutions textures are used nearer the lite, with lower detailed textures employed at bigger distances from the light. The consequence is a more seamless, distortion-gratuitous, transition of shadows beyond a scene.

The technique was improved by Donnelly and Laurizten in 2006 with their variance shadow mapping (VSM) routine, and past Intel in 2022 with their sample distribution algorithm (SDSM).

Game developers often use a battery of shadowing techniques to improve the visuals, simply shadow mapping as a whole rules the roost. However, information technology tin only be applied to a small number of active lite sources, as trying to model information technology to every single surface that reflects or emits light, would grind the frame rate to dust.

Fortunately, in that location is a corking technique that functions well with any object, giving the impression that the lite reaching the object is reduced (considering either itself or other objects are blocking information technology a piddling). The proper noun for this characteristic is ambient apoplexy and there are multiple versions of it. Some have been specifically developed past hardware vendors, for example, AMD created HDAO (high definition ambient occlusion) and Nvidia has HBAO+ (horizon based ambience apoplexy).

Whatsoever version is used, it gets practical later the scene is fully rendered, so it's classed as a post-processing event, and for each pixel the lawmaking substantially calculates how visible that pixel in the scene (see more about how this is done here and here), by comparing the pixel'southward depth value with surrounding pixels in the corresponding location in the depth buffer (which is, once again, stored as a texture).

The sampling of the depth buffer and the subsequent adding of the concluding pixel color play a meaning part in the quality of the ambient occlusion; and just like shadow mapping, all versions of ambient occlusion crave the developer to tweak and accommodate their code, on a case-by-case situation, to ensure the event works correctly.

Washed properly, though, and the impact of the visual effect is profound. In the image higher up, take a close look at the man's artillery, the pineapples and bananas, and the surrounding grass and leafage. The changes in pixel color that the utilize of HBAO+ has produced are relatively minor, just all of the objects now look grounded (in the left, the human being looks like he'south floating above the soil).

Selection any of the recent games covered in this article, and their list of rendering techniques for treatment light and shadow will exist as long as this characteristic slice. And while not every latest 3D title volition boast all of these, the fact that universal game engines, such as Unreal, offering them as options to be enabled, and toolkits from the likes of Nvidia provide code to exist dropped right in, shows that they're not classed as highly specialized, cut-edge methods -- once the preserve of the very all-time programmers, almost anyone can employ the engineering science.

Nosotros couldn't finish this article on lighting and shadowing in 3D rendering without talking well-nigh ray tracing. We've already covered the process in this series, but the electric current employment of the technology demands nosotros accept depression frame rates and an empty depository financial institution residue.

With next generation consoles from Microsoft and Sony supporting it though, that means that within a few years, its use will become another standard tool by developers around the globe, looking to improve the visual quality of their games to cinematic standards. Just look at what Remedy managed with their latest title Control:

We've come a long manner from fake shadows in textures and bones ambient lighting!

There'southward so much more to cover

In this article, we've tried to comprehend some of the fundamental math and techniques employed in 3D games to make them expect as realistic as possible, looking at the engineering behind the modelling of how light interacts with objects and materials. And this has been just a small sense of taste of it all.

For example, we skipped things such as energy conservation lighting, lens flare, bloom, high dynamic rendering, radiance transfer, tonemapping, fogging, chromatic abnormality, photon mapping, caustics, radiosity -- the listing goes on and on. Information technology would take another three or 4 articles just to comprehend them, every bit briefly every bit we have with this feature's content.

We're sure that you've got some great stories to tell about games that have amazed yous with their visual tricks, so when you're diggings your way through Call of Mario: Deathduty Battleyard or like, spare a moment to expect at those graphics and marvel at what's going on backside the scenes to make those images. Yes, it's zilch more than than math and electricity, merely the results are an optical smorgasbord. Any questions: burn them our way, too! Until the next one.

Also Read

- Display Tech Compared: TN vs. VA vs. IPS

- Anatomy of a Graphics Card

- 25 Years Later: A Brief Assay of GPU Processing Efficiency

Source: https://www.techspot.com/article/1998-how-to-3d-rendering-lighting-shadows/

Posted by: westfeacts.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How 3D Game Rendering Works: Lighting and Shadows"

Post a Comment